My new job started off great. My colleagues were nice, I had the flexibility that working moms can only dream of, and I was doing the same thing I had done for the previous decade but with a much larger company – easy peasy, as my daughter says. Once the newness wore off though, it started to get a little more stressful. Though I had spent the prior ten years doing similar work and now had access to resources that my smaller firm never had, it wasn’t a seamless transition. It was a punch to the gut and killed my self-confidence. After all those years in a very similar job working my tail off, why were some things so difficult? I thought, was it me? It must be me. I just wasn’t good enough.

Meanwhile, I decided to seek another opinion on my AVM, just as a precautionary, as the status quo was perfectly fine. I had been so busy adjusting to the new job and adjusting the kids to a new pre-school, I had not spent too much time worrying about that pesky brain problem. But the doctors that I saw in the first round of appointments encouraged me to seek multiple opinions as AVMs are not easy or straightforward and can range from conservative to aggressive on the treatment scale.

I had a few more tests through the fall and winter, a functional MRI (f-MRI) and a WADA test.

For the f-MRI, imagine the claustrophobic feeling of a regular MRI, but then add to that doctors asking questions through speakers in the tube. They still don’t want you to move; they just want you to listen and think, all the while they are monitoring where the blood flows as the brain answers the questions (silently). The questions were along the lines of “think of words that rhyme with book,” “think of as many words as you can that start with the letter t,” and while I made a mental list, they took images of my brain. There were various puzzles and riddles. It was super stressful, not fun at all, and I thought I was going to lose my mind and simultaneously suffocate that day. As I lay in that tube, I worried that I was not answering the questions correctly or that I was doing it all wrong. But there were no right or wrong answers because the doctors had no idea what I was thinking – they were only interested in the parts of the brain that I used to come up with the answers. I was alone that day because Ryan had to pick up the kids from daycare. He didn’t know, and I didn’t know I needed him with me that day. I also needed valium, a heavy dose of valium.

The WADA test was not quite as stressful (no tube, thankfully) but it wasn’t a cakewalk either. This test was done in an operating room at a hospital and involved neurointerventional radiologists, neurologists, and neuropsychologists. I was the least educated person in the room that day. I recall lying there surrounded by at least 12 people, poking and prodding and making sure I was ready. I was holding back tears as they were prepping me for the test. The nurses, trying to make me feel comfortable, started asking me about my kids, how old they were, where they went to pre-school. That didn’t help. I lost it. I was so nervous.

I took a cab to the hospital that morning so Ryan could drop the kids at school. Our babysitter picked them up in the afternoon so Ryan could meet me in the recovery area when the procedure was complete. I really regretted not living closer to family that day. Ryan and I make a great team, and we have had some wonderful babysitters, but there’s nothing like having family around when you’re in full-on freak out mode. I had to put on my game face and suck it up. I survived and I’m now stronger for it.

The WADA test aims to identify language and memory function within the two hemispheres of the brain by putting the two sides of the brain to sleep separately. Here’s what I remember…First, again through the vein in the groin, they injected amytal (otherwise known as truth serum) into one side of the brain, putting that side of the brain to sleep. Then doctors asked me a series of questions, showed me some flashcards and played some music for me. I don’t recall exactly how it worked and timing is a total blur, but what they were trying to figure out was whether the side of the brain that was awake could answer the questions without the help of the sleeping side. They did the same thing on the other hemisphere, once the part of the brain that was initially sleeping woke up, so they could repeat the process. It was wild.

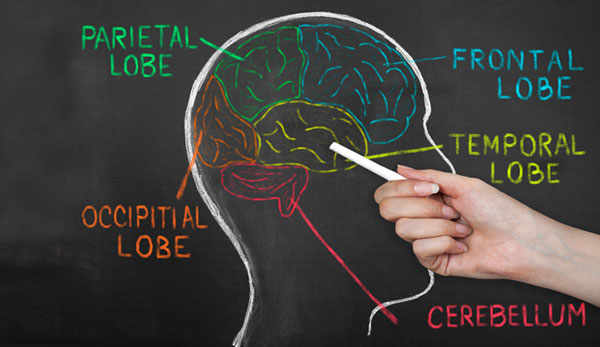

The study showed that when the left hemisphere of the brain was asleep and the right hemisphere, where the AVM resides, had to answer the questions, it could not. I could not recall the flashcards, respond to the questions or recognize the music. However, the left side could complete the tasks without the help of the right side, proving the left side is dominant.

As strange as it sounds, this is good news for me, because when doctors resect the AVM from the brain, brain tissue will come with it, and so it’s important that they don’t take “good brain” out.

After reviewing the results of these tests, the “round two” set of doctors suggested treatment, a staged approach involving injecting a glue-like substance through a vein in my leg, up to the brain, to close off the tangled vessels that way. It would take four or five rounds of this procedure, known as embolization, each replete with procedural risks, requiring a short hospital stay and instructions to “take it easy” for a while after each procedure. At the end of the four or five rounds, we would either consider radiation therapy or a craniotomy, depending on what they would be able to close with embolization. The goal was to embolize as much AVM as possible.

I was bewildered. Why had the first round of doctors given such different advice? Was I supposed to leave it alone or treat it? We had a hard time processing why doctors, each well-known in their fields, affiliated with nationally ranked hospitals, could provide advice on opposite ends of the spectrum.

So I went back to all my notes from conversations with the round one and round two doctors, trying to make sense of it all. There was consistency in a couple of things: 1) the AVM was large and complex and 2) there were two doctors worth seeing for second opinions. Each time the previous doctors mentioned these new doctors, I must have inadvertently dismissed their names because they were on the west coast, one in Phoenix and one in San Francisco. I had access to Boston hospitals, some of the best in the country, why would I go west? But it was evident in my notes (and subsequently confirmed in my research and my online AVM support groups) that these doctors were “famous” in the AVM (and aneurysm) world. Now what?